Posts in Category: What does not work in Science

Scientific conferences at the time of COVID

The social restrictions caused by the pandemic have annihilated the galaxy of scientific conferences as we knew it. Many conferences have tried to move online, in the same way we moved 1-to-1 meetings or teaching online: we applied a linear transposition trying to virtually recreate the very experience we were having when traveling physically (for good and for bad). I would argue that the linear translation of a physical conference to the virtual space, has managed to successfully reproduce almost all of the weaknesses, without, however, presenting almost any of the advantages. This is not surprising because we basically tried to enforce old content to a new medium, ignoring the limits and opportunities that the new medium could offer.

Online conferences like online journals

Something similar happened in science before, when journals transitioned from paper to the web: for years, the transition was nothing more than the digital representation of a printed page (and for many journals, this still holds true). In principle, an online journal is not bound to the physical limitation on the number of pages; it can offer new media experiences besides the classical still figure, such as videos or interactive graphs; it could offer customisable user interfaces allowing the reader to pick their favourite format (figures at the end? two columns? huge fonts?); it does not longer differentiate between main and supplementary figures; it costs less to produce and zero to distribute; etc, etc. Yet – how many journals are currently taking full advantage of these opportunities? The only one that springs to mind is eLife and, interestingly enough, it is not a journal that transitioned online but one that was born online to begin with. Transitions always carry a certain amount of inherent inertia with them and the same inertia was probably at play when we started translating physical conferences to the online world. Rather than focusing on the opportunities that the new medium could offer, we spent countless efforts on try to parrot the physical components that were limiting us. In principle, online conferences:

- Can offer unlimited partecipation: there is no limit to the number of delegates an online conference can accomodate.

- Can reduce costing considerably: there is no need for a venue and no need for catering; no printed abstract book; no need to reimbourse the speakers travel expenses; unlimimted partecipants imply no registrations, and therefore no costs linked to registration itself. This latter creates an interesting paradox: the moment we decide to limit the number of participants, we introduce an activity that then we must mitigate with registration costs. In other words: we ask people to pay so that we can limit their number, getting the worst of both worlds.

- Can work asyncronously to operate on multiple time zones. The actual delivery of a talk does not need to happen live, nor does the discussion.

- Can prompt new formats of deliveries. We are no longer forced to be sitting in a half-lit theatre while following a talk so we may as well abandon video tout-court and transform the talk into a podcast. This is particularly appealing because it moves the focus from the result to its meaning, something that often gets lost in physical conferences.

- Have no limit on the number of speakers or posters! Asyncronous recording means that everyone can upload a video of themselves presenting their data even if just for a few minutes.

- Can offer more thoughtful discussions. People are not forced to come up with a question now and there. They can ask questions at their own pace (i.e. listen to the talk, think about it for hours, then confront themselves with the community).

Instead of focusing on these advantages, we tried to recreate a virtual space featuring “rooms”, lagged video interaction, weird poster presentations, and even sponsored boots.

Practical suggestions for an online conference.

Rather than limit myself to discussing what we could do, I shall try to be more constructive and offer some practical suggestions on how all these changes could be implemented. These are the tools I have just used to organise a dummy, free-of-charge, online conference.

For live streaming: Streamyard

The easiest tool to stream live content to multiple platforms (youtube but also facebook or twitch) is streamyard. The price is very accessible (ranging from free to $40 a month) and the service is fully online meaning that neither the organiser not the speakers need to install any software. The video is streamed online on one or multiple platforms simultaneously meaning that anyone can watch for free simply by going to youtube (or facebook). The tutorial below offers a good overview of the potentiality of this tool. Skip to minute 17 to have an idea of what can be done (and how easily it can be achieved). Once videos are streamed on youtube, they will be automatically saved on their platform and can be accessed just like any other youtube video (note: there are probably other platforms like streamyard I am not aware of. I am not affiliated to them in any way).

For asynchronous discussion and interaction between participants: reddit

Reddit is the most popular platform for asynchronous discussions. It is free to use and properly vetted. It is already widely used to discuss science also in an almost-live fashion called AMA (ask-me-anything). An excellent example of a scientific AMA is this one discussing the discoveries of the Horizon Telescope by the scientist team behind them. Another interesting example is this AMA by Nobel Laureate Randy Sheckman. As you browse through it, focus on the medium, not the content. Reddit AMAs are normally meant for dissemination to the lay public but here we are discussing the opportunity of using them for communication with peers.

A dummy online conference.

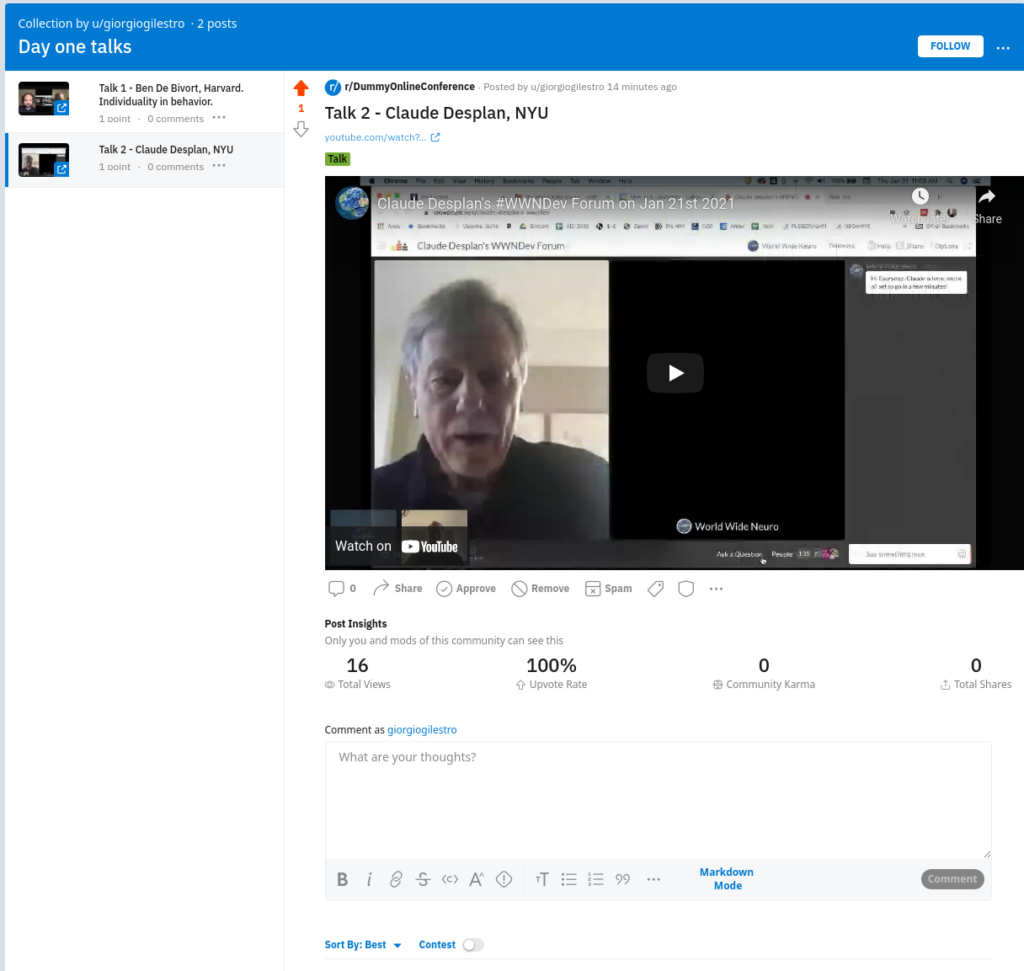

For sake of example, I have just created a dummy conference on reddit while I was writing this post. You can browse it here. My dummy conference at the moment features one video poster and two talks as well as a live lounge for general discussions. All this was put together in less than 10 minutes and it’s absolutely free. Customisation of the interface is possible, with graphics, CSS, flairs, user attributes etc.

Notice how there are no costs of registrations, no mailing lists for reaching participants, no zoom links to join. No expenses whatsoever. The talks would be recorded and streamed live via streamyard while the discussion would happen, live or asynchronously, on reddit. Posters could be uploaded directly by the poster’s authors who would then do an AMA on their data.

An (almost) examples of great success: The Worldwide series of seminars.

Both talks in my dummy conference were taken by the World Wide Neuro seminar series, the neuro branch of the world wide science series. Even though this is seminar series, it is as close as it gets to what an online conference could be and the project really has to be commended for its vision and courage. This is not the online transposition of a physical conference but rather a seminar series born from scratch to be online. Videos are still joined via zoom and the series does lack features of interaction which, in my opinion, could be easily added by merging the videos with reddit as I did in my dummy conference example.

Conclusion.

It is technically possible to create an online conference at absolutely no expense. The tools one can use are well-vetted and easy to use on all sides. This does require a bit of a paradigm shift but it is less laborious and difficult than one may think.

What is wrong with scientific publishing and how to fix it.

Randy Sheckman’s recent decision to boycott the so called glam-mag Cell Nature & Science (CNS) made me realize that I never expressed on this blog my view on the problems with scientific publishing. Here it comes. First, one consideration: there are two distinct problems that have nothing to do with each other. One is the #OA issue, the other is the procedural issue. My solution addresses both but for sake of reasoning let’s start with the latter:

- Peer review is not working fairly. A semi-random selection of two-three reviewers is too unrepresentative of an entire field and more often than not papers will be poorly reviewed.

- As result of 1, the same journal will end up publishing papers ranging anywhere in the scale of quality, from fantastic to disastrous

- As result of 2, the IF of the journal cannot be used to proxy quality of single papers and not even of the average paper because distribution is too skewed (the famous 80/20 problem)

- As result of 3, there is no statistical correlation between a paper published on a high IF journal and its actual value and this is a problem because it’s somehow commonly accepted that there should be one.

- As result of 4, careers and grants are made based on a faulty proxy

- As result of 5, postdocs tend to wait years in the lab hoping to get that one CNS paper that will help them get the job – and obviously there are great incentives to publish fraudulent data for the same reason.

Ok, so let’s assume tomorrow morning CNS cease to exist. They close down. How does this solve the issue? It doesn’t.

CNS are not damaging Science. They are simply sitting on the very top of the ladder of scientific publishing and they receive more attention than any other journal. Remove them from the top and we have just moved the problem a bit down the ladder, next to whatever journal is following. Some people criticise CNS for being great pusher of the IF system; “to start”, they say, “CNS could help by making public the citation data of the single papers and not just the IF as journal aggregate”. This would be an interesting move (scientists love all kind of data) but meaningless to solve the problem. Papers’ quality would still be skewed and knowing the citation number of a single paper will not be necessarily representative of its value because bad papers, fake papers & sexy papers can end up being extremely cited anyway. Also, it takes time for papers to be cited anyway.

So what is the solution? The solution is to abolish pre publication peer review as we know it. Just publish anything and get an optional peer-review as service (PRaaS) if you think your colleagues may help you get a better paper out. This can create peer reviewing companies on the free market and scientists would get paid for professional peer review. When you are ready to submit, you send the paper to a public repository. The repository has no editing service and no printing fees. It’s free and Open Access because costs are anyway minimal. What happens to journals in this model? They still exist but their role is now different. Nature, Cell and Science now don’t deal with the editorial process any longer. Instead, the constantly look through the pool of papers published on the repository and they pick and highlight the ones they think are the best ones, similarly to how a music or a videogame magazine would pick and review for you the latest CD on the markets. They still do their video abstracts, their podcasts, their interviews to the authors, their news and views. They still sell copies but ONLY if they factually add value.

This system solves so many problems:

- The random lottery of the peer review process is no longer

- Nobody will tell you how you have to format your paper or what words you can use in your discussion

- Everything that gets published is automatically OA

- There a no publication fees

- There is still opportunity for making money, only this time in a fair way: scientists make money when they enrol for peer-review as a service; journals still continue to exist.

- Only genuinely useful journals continue to exist: all those thousands of parasitic journals that now exist just because they are easy to publish with, will perish.

Now, this is my solution. Comments are welcome.

The alternative is: I can publish 46 papers on CNS, win the Nobel prize using those papers, become editor of a Journal (elife) that does the very same thing that CNS do and then go out on the Guardian and do my j’accuse.

Postdoc, love or hate? A survey.

Following last week’s discussions about the tough life of a postdoc, I’ve realized more data is needed before making general assumptions on what postdocs want and need. Jennifer Rohn’s post had an overwhelming response of sympathizing postdocs who would love to have a “postdoc for life position” and I didn’t find this surprising. What came a bit unexpected to me, though, is that the other voice was hardly heard.

I think the problem has deeper issues that will have to be solved by completely changing the way we define a laboratory.

For sake of smart discussions, I am setting up a survey aimed at all postdocs out there. You’ll find it here: http://thepostdoctrap.gilest.ro

I am not doing this just because I care about the issue: I have been invited to a meeting organized by the postdocs of the MPI-CBG in late May and I’d love to give those guys some numbers about the issue. So, please, take that survey and come back in couple of months for the results.

I am a postdoc and I think I just realized I have been screwed for years

It seems in the past two weeks someone has started going around lifting big stones in the luxurious and exotic garden of science, finding the obvious gross underneath. To be more precise, the topic being discussed here is: “I am a postdoc and I think I just realized I have been screwed for years“.

A couple of weeks ago, a friend of mine blogged about his decision to leave academia after yet another nervous breakdown. I leave it to his words to describe what it means to realize in your early thirties that your childhood dream won’t become a reality because the job market is broken and you can’t cope with that stress. To be honest, while I sympathize with him, I find his rant extreme, but what is more important than discussing anecdotal experiences is actually the huge number of comments that post had, not only on the blog but also on social discussion websites. Literally hundreds of comments from people who went through similar experiences, culminating with the epiphany that finding a job in academia is freaking difficult.

This discussion is not new, of course. Occasionally people from academia feel the urge to let postdocs and PhD student know that this is a very risky road. See Jonathan Katz’s opinion from back in 2005, for instance.

Why am I (a tenured professor of physics) trying to discourage you from following a career path which was successful for me? Because times have changed (I received my Ph.D. in 1973, and tenure in 1976). […] American universities train roughly twice as many Ph.D.s as there are jobs for them. When something, or someone, is a glut on the market, the price drops. In the case of Ph.D. scientists, the reduction in price takes the form of many years spent in “holding pattern” postdoctoral jobs. Permanent jobs don’t pay much less than they used to, but instead of obtaining a real job two years after the Ph.D. (as was typical 25 years ago) most young scientists spend five, ten, or more years as postdocs. They have no prospect of permanent employment and often must obtain a new postdoctoral position and move every two years.

Pretty actual, isn’t it? Although these arguments do emerge now and then, they do it way less than they should¹. Why? The main reason is that PIs have really nothing to gain from changing the current situation: as it is now, they find the field overcrowded with postdocs who cannot do anything else but staying in the lab, hoping to get more papers than their competitors; waiting for the unlucky ones to drop out to reduce competition. That means it’s easy for the PIs to get postdocs for cheap and keep them in the lab as long as possible.

Of course there could be an even better scenario for PIs: postdocs who never leave the lab! Let’s face it: having so many postdocs to choose from is nice, but many of them aren’t actually that good and also it takes time for them to acquire certain skills. So why don’t give them the chance to stay for 20 years in the same lab? This is exactly what Jennifer Rohn was advocating on Nature last week. I think in her editorial Jennifer actually rightly identifies the problem:

The system needs only one replacement per lab-head position, but over the course of a 30–40-year career, a typical biologist will train dozens of suitable candidates for the position. The academic opportunities for a mature postdoc some ten years after completing his or her PhD are few and far between.

But she fails to provide the right solution:

An alternative career structure within science that professionalizes mature postdocs would be better. Permanent research staff positions could be generated and filled with talented and experienced postdocs who do not want to, or cannot, lead a research team — a job that, after all, requires a different skill set. Every academic lab could employ a few of these staff along with a reduced number of trainees. Although the permanent staff would cost more, there would be fewer needed: a researcher with 10–20 years experience is probably at least twice as efficient as a green trainee.

I cannot even start saying how full of rage this attitude makes me. This position is so despicable to me! Postdoc positions exist, on the first place, because they provide a buffer for all those who would like to get a professor job but cannot, due to the limited market. Any economist would tell you that the solution is not to transform this market into something even more static but to increase mobility, for Newton’s sake! Sure, some postdocs may realize too late they don’t really want to be independent and they would gladly keep doing what they are doing for some more time: this is what positions in industry are for², and this is what a lab tech position is for. No need to invent new names for those jobs.

So, here I propose an alternative solution: what about giving postdocs the chance of being independent, without necessarily being bound to running a 4 people lab to start with, or without the need to hold a tenure position? What about redistributing resources so that current PIs will have a smaller lab so that 1 or 2 more people somewhere else could have the chance to start their own career? Isn’t this more fair?

I wrote about this before, so I won’t repeat myself: in short, the big lab model is not sustainable anymore and it is not fair!

The problem, Jennifer, is not that postdoc want to stay longer in the lab: the problem is that they want out!

Notes

1: a recurrent question in the new Open Science society is “should scientists be blogging?“. My answer is yes, definitely (in fact, that’s what I am doing) but I don’t expect them to blog about their opinion on the last paper in their field. I don’t think that is so useful, actually. I’d rather have them talk about their daily life as scientists and speak freely and loudly about controversial issue.

2: My wife is one of them: she realized she didn’t want to have anything to do with academia anymore and she moved to industry where she actually got a salary that was more than twice the one she was getting in the University doing pretty much the same job, without worrying about fellowships and competition. She has never been so happy at work, too.

What has changed in science and what must change.

I frequently have discussions about funding in Science (who doesn’t?) but I realized I never really formalized my ideas about it. It makes sense to do that here. A caveat before I start is that everything I write about here concerns the field of bio/medical sciences for those are the ones I know. Other fields may work in different ways. YMMV.

First of all, I think it is worth noticing that this is an extremely hot topic, yet not really controversial among scientists. No matter whom you talk to, not only does everyone agree that the status quo is completely inadequate but there also seem to be a consensus on what kind of things need to be done and how. In particular, everyone agrees that

- more funding is needed

- the current ways of distributing funding and measuring performance are less than optimal

When everybody agrees on what has to be done but things are not changing it means the problem is bigger than you’d think. In this post I will try to dig deeper into those two points, uncovering aspects which, in my opinion, are even more fundamental and controversial.

Do we really need more funding?

The short answer is yes but the long answer is no. Here is the paradox explained. Science has changed dramatically in the past 100, 50 (or even 10) years, mainly because it advances at a speedier pace than anything else in human history and simply enough we were (and are) not ready for this. This is not entirely our fault since, by definition, every huge scientific breakthrough comes as a utter surprise and we cannot help but be unprepared to its consequences¹. We did adapt to some of the changes but we did it badly and we did not do it for all to many aspects we had to. In short, everyone is aware about the revolution science has had in the past decades, yet no one has ever heard of a similar revolution in the way science is done.

A clear example of something we didn’t change but we should is the fundamental structure of Universities. In fact, that didn’t change much in the past 1000 years if you think about it. Universities still juggle between teaching and research and it is still mainly the same people who does both. This is a huge mistake. Everybody knows those things have nothing in common and there is no reason whatsoever for them to lie under the same roof. Most skilled researchers are awful teachers and viceversa and we really have no reason to assume it should not be this way Few institutions in the world concentrate fully on research or only teaching but this should not be the exception, it should be the rule. Separating teaching and research should be the first step to really be able to understand the problems and allocate resources.

Tenure must also be completely reconsidered. Tenure was initially introduced as a way to guarantee academic freedom of speech and action. It was an incentive for thoughtful people to take a position on controversial issues and raise new ones. It does not serve this role anymore: you will get sacked if you claim something too controversial (see Lawrence Summers’ case) and your lab will not receive money if you are working on something too exotic or heretic. Now, I am not saying this is a good or a bad thing. I am just observing that the original meaning of tenure is gone. Freedom of speech is something that should be guaranteed to everyone, not just academic, through constitutional laws and freedom of research is not guaranteed by tenure anyway because you don’t get money to do research from your university, you just get your salary. It’s not 1600 anymore, folks.

Who is benefiting from tenure nowadays? Mainly people who have no other meaning of paying their own salary, that is researchers who are not active or poorly productive and feel no obligation to do so because they will get their salary at the end of the month anyway. This is the majority of academic people not only in certain less developed countries – like Italy, sigh – but pretty much everywhere. Even in the US or UK or Germany many departments are filled with people who publish badly or scarcely. Maybe they were good once, or maybe it was easier at their time to get a job. Who pays for their priviledge? The younger generation, of course.

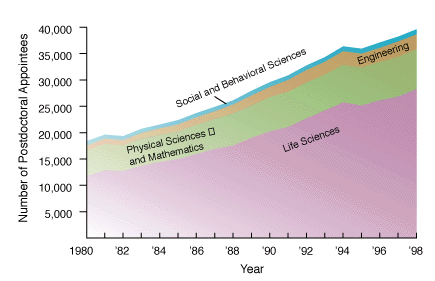

The number of people entering science grows every year², especially in the life sciences. The number of academic position and the funding extent is far from being sufficient to cover current needs. In fact, about 1-2 in 10 postdoc will manage to find a job as professor and among those who do, funding success rate is again 20-30% in a good year. In short, even if we were to increase the scientific budget by 5 times tomorrow morning that would still not be enough. This means that even though it would be sure nice to have more money, it’s utopia to think this will help. Indeed, we need to revolutionize everything, really. People who have tenure should not count on it anymore and they should be ready to leave their job to somebody else. There is no other way, sorry.

Do we really need better forms of scientific measurement?

No. We need completely new forms of scientific measurement. And we need to change the structure of the lab. Your average successful lab is composed of 10 to 30 members, most of them PhD students or postdocs. They are the ones who do the work, without doubts. In many cases, they are the ones who do the entire work not only without their boss, but even despite the boss. This extreme eventuality is not the rule, of course, but the problem is: there is no way to tell it apart! The principal investigator as they say in the USA, or the group leader as it is called with less hypocrisy in Europe, will spend all of their time writing grants to be funded, speaking at conferences about work they didn’t do, writing or merely signing papers. Of course leading a group takes some rare skills, but those are not the skill of a scientist they are the skills of a manager. The system as it is does not reward good scientists, it rewards good managers. You can exploit creativity of the people working for you and be succesful enough to keep receiving money and be recognized as a leader but you are feeding a rotten process. Labs keep growing in size because postdocs don’t have a chance to start their own lab and because their boss uses their work to keep getting the money their postdoc should be getting instead. This is an evil loop.

This is a problem that scientometrics cannot really solve because it’s difficult enough to grasp the importance of a certain discovery, let alone the actual intellectual contribution behind it. It would help to rank laboratories not just by number of good publications, but by ratio between good papers and number of lab members. If you have 1 good paper every second year and you work alone, you should be funded more than someone who has 4 high publications every year but has a group of 30 people.

Some funding agencies, like HHMI, MRC and recently WellcomeTrust, decided to jump the scientometric problem and fund groups independently of their research interest: they say “if you prove to be exceptionally good, we give you loads of money and trust your judgement”. While this is a commendable approach, I would love to see how those labs would rank when you account for number of people: a well funded lab will attract the best sutudents and postdocs and good lab members make a lab well funded. Here you go with an evil loop again.

In gg-land, the imaginary nation I am supreme emperor of, you can have a big lab but you must really prove you deserve it. Also, there are no postdocs as we know them. Labs have students who learn what it means to do science. After those 3-5 years either you are ready to take the leap and do your stuff by yourself or you’ll never be ready anyway. Don’t kid yourself. Creativity is not something you can gain with experience; if at all, it’s the other way around: the older you get, the less creative you’ll be.

Some good places had either a tradition (LMB, Bell labs) or have the ambition (Janelia) of keeping group small and do science the way it should be done. Again, this should not be the exception. It should be the rule. I salute with extreme interest the proliferation of junior research fellowships also known as independent postdoc positions. They are not just my model of how you do a postdoc. In fact they are my model of how you do science tout court. Another fun thing about doing science with less resource is that you really have to think more than twice about what you need and spend your money more wisely. Think of the difference between buying your own bike or building one from scratch. You may start pedaling first if you buy one, but only in the second case you will have a chance to build a bike that run faster and better. On the long run, you may well win the race (of course you should never reinvent the wheel; it’s OK to buy those).

Of course, the big advantage of having many small labs over few big is that you get to fund different approaches too. As our grandmother used to say: it’s not good to keep all eggs in the same basket. As it happens in evolution, you have to diversify, in science too³.

What can we (scientists) do? Bad news is, I don’t think these are problems that can be solved by scientists. You cannot expect unproductive tenure holders to give up their job. You cannot expect a young group leader to say no to tenure, now that they are almost there. You cannot expect a big lab to agree in reducing the number of people. Sure, all of them complaint that they spend their times writing grants and cannot do the thing they love the most – experiments! – anymore because too busy. If you were to give them the chance to go back to the bench again, they would prove as useless as an undergrad. They are not scientists anymore, they are managers. These are problem that only funding agencies can solve, pushed by those who have no other choice that asking for a revolution, i.e.: the younger generation.

Notes:

1. Surprise is, I believe, the major difference between science and technology. The man on the moon is technology and we didn’t get there by surprise. Penicillin is science and comes out of the blue, pretty much.

2. Figure is taken from Mervis, Science 2000. More recent data on the NSF website, here.

3. See Michael Nielsen’s post about this basic concept of life.

Update:

Both Massimo Sandal and Bjoern Brembs wrote a post in reply to this, raising some interesting points. My replies are in their blogs as comments.

What does it take to make a good Scientist?

I just saw something on the weekly edition of Nature Jobs that made me very happy. It is something that I was waiting to see since a long time. In May 2006 Georgia Chenevix-Trench felt like sharing some of her wisdom with the youngest public of the journal Nature. In the (often embarrassing) portion of the journal called Nature Jobs, she published a Decalogue with “tips for students”; goal of the letter was to provide prospective PhD students with rules of thumbs that would help out having a successful career. Sadly enough most of them were embracing the concept of hard work and only marginally important skills such as creativity, imagination, collaborative science.

I just saw something on the weekly edition of Nature Jobs that made me very happy. It is something that I was waiting to see since a long time. In May 2006 Georgia Chenevix-Trench felt like sharing some of her wisdom with the youngest public of the journal Nature. In the (often embarrassing) portion of the journal called Nature Jobs, she published a Decalogue with “tips for students”; goal of the letter was to provide prospective PhD students with rules of thumbs that would help out having a successful career. Sadly enough most of them were embracing the concept of hard work and only marginally important skills such as creativity, imagination, collaborative science.