Posts Tagged: creativity

Of scientists and entrepreneurs.

Prepare to jump. Jump.

As my trusty 25 readers would know, a few months ago I made the big career jump and moved from being on the bench side of science to the desk side, becoming what is called a Principal Investigator (PI). As a matter of fact nothing really seems to have changed so far: I hold a research fellow position at Imperial College, meaning that I am a one-man lab: I still have to plan and execute my experiments, still have to write my papers and deal with them, still have to organize my future employment – all exactly as I was doing before.

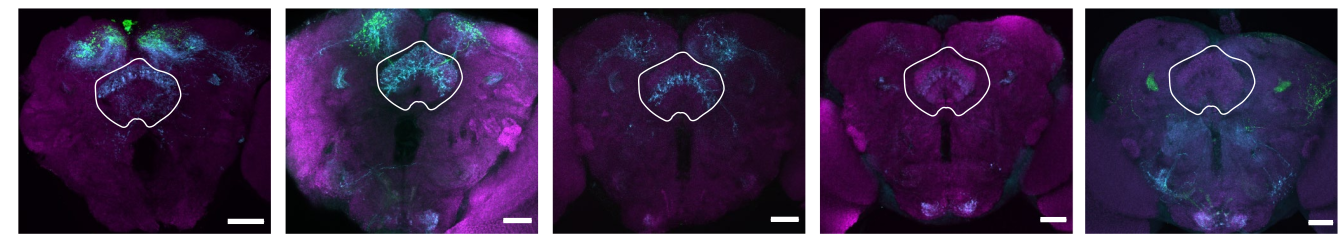

Me, in my lab. Feb 2011

However, starting your own lab is still a formalization of walking with your own legs and, as such, one must be prepared to encounter new challenges. Unfortunately no one really ever prepared me to this: we spend a great deal of time as PhD and Postdocs learning skills that not necessarily will help for the next steps and when the moment comes to be really independent, a lot of people feel lost in translation. This may bring frustration in the PI (who find themselves completely unprepared for the new role) and in their students (who find themselves led by someone who is completely unprepared for their role). I saw this happening countless times.

Scared by the idea of ending up like this, I actually started thinking about how things would evolve quite some time ago. It’s easy: you just take inspiration from PIs around you. You start with all those who work in the same institute or department, for instance. And you try to figure out what they do right and what they do wrong, and learn by Bayesian inference: I like that, I don’t like this, I want to be like that, I don’t want to be like this. If you are more of a textbook person, you can also get yourself one of those “How to be a successful PI” guidebook; they are particular popular in the USA and some people find them helpful. Did that too, found it a bit dumb.

Look around.

Finally, there is a third strategy you may want to follow and that is: find inspiration and stories of success in people who are doing things completely different from what you do. The rational of this strategy lays in the assumption that certain people will be good in what they do, no matter what that is. They have special skills that make them succesful, whether they are running a research lab or a law firm or a construction business. A good gymnasium (in the greek sense of the world) to get in touch with such people is the entrepreneur world. There are several analogies between being the founder of a, let’s say, computer startup and being a newly appointed PI. Here are some examples out of the tip of my head:

- both need to believe in themselves and in what they do, more than anybody else around them

- both need to convince people that what they want to do is worth their investment money, whether they are millions of venture capitals or bread-crumbs of research grant money

- both have to choose very carefully the people they will work with

- both have to find their niche in a very competitive market or else, if they will rather go after the big competition, they need to make sure their product is better in quality and/or appeal

- both need to innovate and always be ahead of competition

- they both chose their career because they enjoy being bosses of themselves (or at least they better do)

- both need to learn how to overcome difficult times by themselves (“loop to point 1” is one solution)

- et cetera

If you are not yet convinced about this, read this essay by angel investor Paul Graham titled “What we look for in founders“. If I were to substitute the world “founder” with “scientist”, you would not even notice.

These are the reasons why a couple of years ago I started following the main community of startup founders in the web, hackernews. It’s a social community composed of people with a knack for entrepreneurship – some of them extremely succesful (read $$$ in their world). Most of them are computer geeks, which is good for my purposes as it is yet another category of people who share a lot with scientists, namely: social inepts who’d love to improve their relationship skills but dedicate way too much time to work.

So the question now is: what did I learn from them? To begin, I reinforced my prejudice: that scientists and entrepreneurs have a lot in common and that certain people would be succesful in anything they would do. This is a crucial starting point because you’ll find that there is way more information on how to be a succesful entrepreneur than how to be a succesful academic – I still don’t have a good explanation on why it is so, actually. The moment you accept that, your sample case just grew esponentially and you have much more material for your inference based learning. I am no longer just limited at taking inspiration from other scientists, but also succesful companies. This is actually not so obvious to most people. For instance, every now and then a new research institute is born with the great ambition of being the next big thing. The decide to follow the path of those institutes who succeded in the past, assuming there is something magic in their recipy and because the sample set is limited they always end up naming the same names: LMB, CSHL, EMBL, Carnegie… Why nobody takes Google as an example? Or Apple? Or IBM? I am actually deeply convinced that if Google were to create a Google Research Institute, they would be amazingly succesful. They have already made exciting breakthrough in (published!) research with Google Flu Trends or Google Book Projects. If they were to philantropically extend their research interests to other fields, they’ll make a lot of people bite their dust (I’d kill to work at a Google Research Institute, by the way. wink wink.).

Five examples of relevant things I learned by looking at the entrepreneur world.

1. Talking about Google, I found extremely smart their philosophy to incentivate people to work 20% of their time on something completely unrelated to their project. Quoting wikipedia:

As a motivation technique, Google uses a policy often called Innovation Time Off, where Google engineers are encouraged to spend 20% of their work time on projects that interest them. Some of Google’s newer services, such as Gmail, Google News, Orkut, and AdSense originated from these independent endeavors.[177] In a talk at Stanford University, Marissa Mayer, Google’s Vice President of Search Products and User Experience, showed that half of all new product launches at the time had originated from the Innovation Time Off.[178]

The irony behind this, actually, is that I am willing to bet my pants that this idea was in fact borrowed from academia: or better, from how it should be in academia but it’s not anymore.

2. Freedom is the main reason why I chose the academic path and I find people who know how to appreciate freedom (and make it fruitful) very inspirational. See for instance this essay by music entrepreneur Derek Sivers on “Is there such a thing as too much freedom?” or his “Delegate or die“.

3. On a different note, I appreciate tips on how to deal with hiring people. See for instance “How to reject a job candidate without being an asshole“. I wish more people would follow this example. Virtually no one in academia will ever tell you why you didn’t get their job, even though it’s every scientist’s duty to give direct straight feedbacks about other people’s work (it is in fact the very essence of peer reviewing!). I was on the job market last year for a tenure track position and it was a very tough year, in terms of competition. The worst ever, apparently. Each open position had at least 100 or 200 applicants of which half a dozen on average were then called for interview. I had a very high success rate in terms of interviews selections, being called to something like 15 places out of 50 applications sent. Many of them happened to be the best places in the world. In many of them didn’t work out and NONE of them offered any kind of feedback on the interviewed applicants. NONE of them actually took the time to say “this is what didn’t convince us about your interview”. What a shame.

4. I am not that kind of scientist who aim to spend his entire career on one little aspect of something; I enjoy taking new roads (talking about freedom again, I guess). So companies like Amazon or Apple, constantly changing their focus, are of great inspirations.

5. Startup founders know two unwritten rules “Execution is more important than the idea” and “someone else is probably working on the same thing you are”. Read about facebook story to grasp what I am talking about. Here’s is also well summarized (forget point 3 though, that doesn’t apply to science I believe).

6. Finally, as someone who starts with a tiny budget and who has a passion for frugality, I found the concept of ramen profitability very interesting: think big, but start small. That’s exactly what I am doing right now.