Posts Tagged: academia

Of scientists and entrepreneurs.

Prepare to jump. Jump.

As my trusty 25 readers would know, a few months ago I made the big career jump and moved from being on the bench side of science to the desk side, becoming what is called a Principal Investigator (PI). As a matter of fact nothing really seems to have changed so far: I hold a research fellow position at Imperial College, meaning that I am a one-man lab: I still have to plan and execute my experiments, still have to write my papers and deal with them, still have to organize my future employment – all exactly as I was doing before.

Me, in my lab. Feb 2011

However, starting your own lab is still a formalization of walking with your own legs and, as such, one must be prepared to encounter new challenges. Unfortunately no one really ever prepared me to this: we spend a great deal of time as PhD and Postdocs learning skills that not necessarily will help for the next steps and when the moment comes to be really independent, a lot of people feel lost in translation. This may bring frustration in the PI (who find themselves completely unprepared for the new role) and in their students (who find themselves led by someone who is completely unprepared for their role). I saw this happening countless times.

Scared by the idea of ending up like this, I actually started thinking about how things would evolve quite some time ago. It’s easy: you just take inspiration from PIs around you. You start with all those who work in the same institute or department, for instance. And you try to figure out what they do right and what they do wrong, and learn by Bayesian inference: I like that, I don’t like this, I want to be like that, I don’t want to be like this. If you are more of a textbook person, you can also get yourself one of those “How to be a successful PI” guidebook; they are particular popular in the USA and some people find them helpful. Did that too, found it a bit dumb.

Look around.

Finally, there is a third strategy you may want to follow and that is: find inspiration and stories of success in people who are doing things completely different from what you do. The rational of this strategy lays in the assumption that certain people will be good in what they do, no matter what that is. They have special skills that make them succesful, whether they are running a research lab or a law firm or a construction business. A good gymnasium (in the greek sense of the world) to get in touch with such people is the entrepreneur world. There are several analogies between being the founder of a, let’s say, computer startup and being a newly appointed PI. Here are some examples out of the tip of my head:

- both need to believe in themselves and in what they do, more than anybody else around them

- both need to convince people that what they want to do is worth their investment money, whether they are millions of venture capitals or bread-crumbs of research grant money

- both have to choose very carefully the people they will work with

- both have to find their niche in a very competitive market or else, if they will rather go after the big competition, they need to make sure their product is better in quality and/or appeal

- both need to innovate and always be ahead of competition

- they both chose their career because they enjoy being bosses of themselves (or at least they better do)

- both need to learn how to overcome difficult times by themselves (“loop to point 1” is one solution)

- et cetera

If you are not yet convinced about this, read this essay by angel investor Paul Graham titled “What we look for in founders“. If I were to substitute the world “founder” with “scientist”, you would not even notice.

These are the reasons why a couple of years ago I started following the main community of startup founders in the web, hackernews. It’s a social community composed of people with a knack for entrepreneurship – some of them extremely succesful (read $$$ in their world). Most of them are computer geeks, which is good for my purposes as it is yet another category of people who share a lot with scientists, namely: social inepts who’d love to improve their relationship skills but dedicate way too much time to work.

So the question now is: what did I learn from them? To begin, I reinforced my prejudice: that scientists and entrepreneurs have a lot in common and that certain people would be succesful in anything they would do. This is a crucial starting point because you’ll find that there is way more information on how to be a succesful entrepreneur than how to be a succesful academic – I still don’t have a good explanation on why it is so, actually. The moment you accept that, your sample case just grew esponentially and you have much more material for your inference based learning. I am no longer just limited at taking inspiration from other scientists, but also succesful companies. This is actually not so obvious to most people. For instance, every now and then a new research institute is born with the great ambition of being the next big thing. The decide to follow the path of those institutes who succeded in the past, assuming there is something magic in their recipy and because the sample set is limited they always end up naming the same names: LMB, CSHL, EMBL, Carnegie… Why nobody takes Google as an example? Or Apple? Or IBM? I am actually deeply convinced that if Google were to create a Google Research Institute, they would be amazingly succesful. They have already made exciting breakthrough in (published!) research with Google Flu Trends or Google Book Projects. If they were to philantropically extend their research interests to other fields, they’ll make a lot of people bite their dust (I’d kill to work at a Google Research Institute, by the way. wink wink.).

Five examples of relevant things I learned by looking at the entrepreneur world.

1. Talking about Google, I found extremely smart their philosophy to incentivate people to work 20% of their time on something completely unrelated to their project. Quoting wikipedia:

As a motivation technique, Google uses a policy often called Innovation Time Off, where Google engineers are encouraged to spend 20% of their work time on projects that interest them. Some of Google’s newer services, such as Gmail, Google News, Orkut, and AdSense originated from these independent endeavors.[177] In a talk at Stanford University, Marissa Mayer, Google’s Vice President of Search Products and User Experience, showed that half of all new product launches at the time had originated from the Innovation Time Off.[178]

The irony behind this, actually, is that I am willing to bet my pants that this idea was in fact borrowed from academia: or better, from how it should be in academia but it’s not anymore.

2. Freedom is the main reason why I chose the academic path and I find people who know how to appreciate freedom (and make it fruitful) very inspirational. See for instance this essay by music entrepreneur Derek Sivers on “Is there such a thing as too much freedom?” or his “Delegate or die“.

3. On a different note, I appreciate tips on how to deal with hiring people. See for instance “How to reject a job candidate without being an asshole“. I wish more people would follow this example. Virtually no one in academia will ever tell you why you didn’t get their job, even though it’s every scientist’s duty to give direct straight feedbacks about other people’s work (it is in fact the very essence of peer reviewing!). I was on the job market last year for a tenure track position and it was a very tough year, in terms of competition. The worst ever, apparently. Each open position had at least 100 or 200 applicants of which half a dozen on average were then called for interview. I had a very high success rate in terms of interviews selections, being called to something like 15 places out of 50 applications sent. Many of them happened to be the best places in the world. In many of them didn’t work out and NONE of them offered any kind of feedback on the interviewed applicants. NONE of them actually took the time to say “this is what didn’t convince us about your interview”. What a shame.

4. I am not that kind of scientist who aim to spend his entire career on one little aspect of something; I enjoy taking new roads (talking about freedom again, I guess). So companies like Amazon or Apple, constantly changing their focus, are of great inspirations.

5. Startup founders know two unwritten rules “Execution is more important than the idea” and “someone else is probably working on the same thing you are”. Read about facebook story to grasp what I am talking about. Here’s is also well summarized (forget point 3 though, that doesn’t apply to science I believe).

6. Finally, as someone who starts with a tiny budget and who has a passion for frugality, I found the concept of ramen profitability very interesting: think big, but start small. That’s exactly what I am doing right now.

What has changed in science and what must change.

I frequently have discussions about funding in Science (who doesn’t?) but I realized I never really formalized my ideas about it. It makes sense to do that here. A caveat before I start is that everything I write about here concerns the field of bio/medical sciences for those are the ones I know. Other fields may work in different ways. YMMV.

First of all, I think it is worth noticing that this is an extremely hot topic, yet not really controversial among scientists. No matter whom you talk to, not only does everyone agree that the status quo is completely inadequate but there also seem to be a consensus on what kind of things need to be done and how. In particular, everyone agrees that

- more funding is needed

- the current ways of distributing funding and measuring performance are less than optimal

When everybody agrees on what has to be done but things are not changing it means the problem is bigger than you’d think. In this post I will try to dig deeper into those two points, uncovering aspects which, in my opinion, are even more fundamental and controversial.

Do we really need more funding?

The short answer is yes but the long answer is no. Here is the paradox explained. Science has changed dramatically in the past 100, 50 (or even 10) years, mainly because it advances at a speedier pace than anything else in human history and simply enough we were (and are) not ready for this. This is not entirely our fault since, by definition, every huge scientific breakthrough comes as a utter surprise and we cannot help but be unprepared to its consequences¹. We did adapt to some of the changes but we did it badly and we did not do it for all to many aspects we had to. In short, everyone is aware about the revolution science has had in the past decades, yet no one has ever heard of a similar revolution in the way science is done.

A clear example of something we didn’t change but we should is the fundamental structure of Universities. In fact, that didn’t change much in the past 1000 years if you think about it. Universities still juggle between teaching and research and it is still mainly the same people who does both. This is a huge mistake. Everybody knows those things have nothing in common and there is no reason whatsoever for them to lie under the same roof. Most skilled researchers are awful teachers and viceversa and we really have no reason to assume it should not be this way Few institutions in the world concentrate fully on research or only teaching but this should not be the exception, it should be the rule. Separating teaching and research should be the first step to really be able to understand the problems and allocate resources.

Tenure must also be completely reconsidered. Tenure was initially introduced as a way to guarantee academic freedom of speech and action. It was an incentive for thoughtful people to take a position on controversial issues and raise new ones. It does not serve this role anymore: you will get sacked if you claim something too controversial (see Lawrence Summers’ case) and your lab will not receive money if you are working on something too exotic or heretic. Now, I am not saying this is a good or a bad thing. I am just observing that the original meaning of tenure is gone. Freedom of speech is something that should be guaranteed to everyone, not just academic, through constitutional laws and freedom of research is not guaranteed by tenure anyway because you don’t get money to do research from your university, you just get your salary. It’s not 1600 anymore, folks.

Who is benefiting from tenure nowadays? Mainly people who have no other meaning of paying their own salary, that is researchers who are not active or poorly productive and feel no obligation to do so because they will get their salary at the end of the month anyway. This is the majority of academic people not only in certain less developed countries – like Italy, sigh – but pretty much everywhere. Even in the US or UK or Germany many departments are filled with people who publish badly or scarcely. Maybe they were good once, or maybe it was easier at their time to get a job. Who pays for their priviledge? The younger generation, of course.

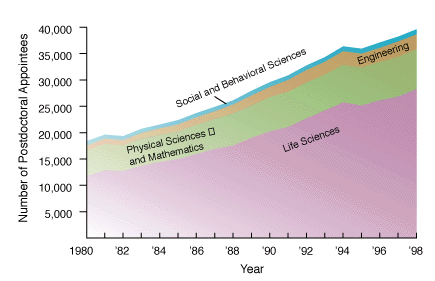

The number of people entering science grows every year², especially in the life sciences. The number of academic position and the funding extent is far from being sufficient to cover current needs. In fact, about 1-2 in 10 postdoc will manage to find a job as professor and among those who do, funding success rate is again 20-30% in a good year. In short, even if we were to increase the scientific budget by 5 times tomorrow morning that would still not be enough. This means that even though it would be sure nice to have more money, it’s utopia to think this will help. Indeed, we need to revolutionize everything, really. People who have tenure should not count on it anymore and they should be ready to leave their job to somebody else. There is no other way, sorry.

Do we really need better forms of scientific measurement?

No. We need completely new forms of scientific measurement. And we need to change the structure of the lab. Your average successful lab is composed of 10 to 30 members, most of them PhD students or postdocs. They are the ones who do the work, without doubts. In many cases, they are the ones who do the entire work not only without their boss, but even despite the boss. This extreme eventuality is not the rule, of course, but the problem is: there is no way to tell it apart! The principal investigator as they say in the USA, or the group leader as it is called with less hypocrisy in Europe, will spend all of their time writing grants to be funded, speaking at conferences about work they didn’t do, writing or merely signing papers. Of course leading a group takes some rare skills, but those are not the skill of a scientist they are the skills of a manager. The system as it is does not reward good scientists, it rewards good managers. You can exploit creativity of the people working for you and be succesful enough to keep receiving money and be recognized as a leader but you are feeding a rotten process. Labs keep growing in size because postdocs don’t have a chance to start their own lab and because their boss uses their work to keep getting the money their postdoc should be getting instead. This is an evil loop.

This is a problem that scientometrics cannot really solve because it’s difficult enough to grasp the importance of a certain discovery, let alone the actual intellectual contribution behind it. It would help to rank laboratories not just by number of good publications, but by ratio between good papers and number of lab members. If you have 1 good paper every second year and you work alone, you should be funded more than someone who has 4 high publications every year but has a group of 30 people.

Some funding agencies, like HHMI, MRC and recently WellcomeTrust, decided to jump the scientometric problem and fund groups independently of their research interest: they say “if you prove to be exceptionally good, we give you loads of money and trust your judgement”. While this is a commendable approach, I would love to see how those labs would rank when you account for number of people: a well funded lab will attract the best sutudents and postdocs and good lab members make a lab well funded. Here you go with an evil loop again.

In gg-land, the imaginary nation I am supreme emperor of, you can have a big lab but you must really prove you deserve it. Also, there are no postdocs as we know them. Labs have students who learn what it means to do science. After those 3-5 years either you are ready to take the leap and do your stuff by yourself or you’ll never be ready anyway. Don’t kid yourself. Creativity is not something you can gain with experience; if at all, it’s the other way around: the older you get, the less creative you’ll be.

Some good places had either a tradition (LMB, Bell labs) or have the ambition (Janelia) of keeping group small and do science the way it should be done. Again, this should not be the exception. It should be the rule. I salute with extreme interest the proliferation of junior research fellowships also known as independent postdoc positions. They are not just my model of how you do a postdoc. In fact they are my model of how you do science tout court. Another fun thing about doing science with less resource is that you really have to think more than twice about what you need and spend your money more wisely. Think of the difference between buying your own bike or building one from scratch. You may start pedaling first if you buy one, but only in the second case you will have a chance to build a bike that run faster and better. On the long run, you may well win the race (of course you should never reinvent the wheel; it’s OK to buy those).

Of course, the big advantage of having many small labs over few big is that you get to fund different approaches too. As our grandmother used to say: it’s not good to keep all eggs in the same basket. As it happens in evolution, you have to diversify, in science too³.

What can we (scientists) do? Bad news is, I don’t think these are problems that can be solved by scientists. You cannot expect unproductive tenure holders to give up their job. You cannot expect a young group leader to say no to tenure, now that they are almost there. You cannot expect a big lab to agree in reducing the number of people. Sure, all of them complaint that they spend their times writing grants and cannot do the thing they love the most – experiments! – anymore because too busy. If you were to give them the chance to go back to the bench again, they would prove as useless as an undergrad. They are not scientists anymore, they are managers. These are problem that only funding agencies can solve, pushed by those who have no other choice that asking for a revolution, i.e.: the younger generation.

Notes:

1. Surprise is, I believe, the major difference between science and technology. The man on the moon is technology and we didn’t get there by surprise. Penicillin is science and comes out of the blue, pretty much.

2. Figure is taken from Mervis, Science 2000. More recent data on the NSF website, here.

3. See Michael Nielsen’s post about this basic concept of life.

Update:

Both Massimo Sandal and Bjoern Brembs wrote a post in reply to this, raising some interesting points. My replies are in their blogs as comments.