Stress, Not Sleep Loss, Drives Intestinal Oxidative Damage and Mortality

The Century-Long Confusion

For over 125 years, scientists have believed that sleep deprivation is lethal. This idea traces back to 1894, when Russian researcher Maria Manaseina made a shocking discovery: puppies forced to stay awake died within just 4-5 days. She declared that “complete absence of sleep is much more fatal for animals than the absolute absence of food”—a statement that has echoed through scientific literature ever since.

But what if we’ve been wrong this entire time?

The problem with sleep deprivation research has always been methodological. How do you keep an animal awake without stressing it? Early researchers resorted to increasingly creative—and harsh—methods: constant poking, forced walking, loud noises, even electric shocks.

When animals died, scientists assumed it was from lack of sleep. But even pioneering sleep researcher Nathaniel Kleitman worried in 1928 that he couldn’t tell “to what extent the effects were due to lack of sleep, and to what extent to muscular fatigue.” This confusion persisted for decades. Even the famous experiments by Allan Rechtschaffen in the 1980s—considered the gold standard of sleep deprivation research—used a method that constantly disturbed rats on a slowly rotating disk. When the rats died after 2-3 weeks, everyone assumed sleep loss was the culprit.

The ROS Revolution: A Breakthrough Discovery

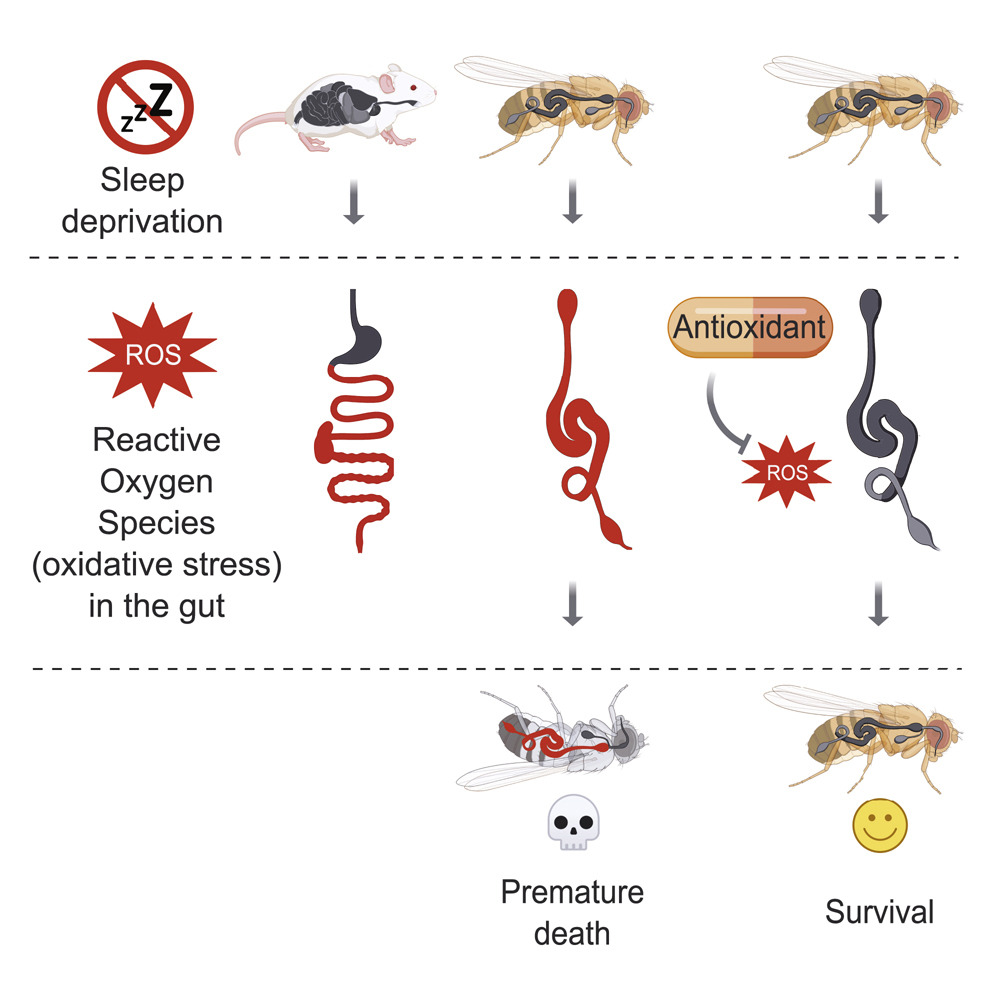

In 2020, a landmark study by Vaccaro and colleagues at Harvard Medical School made what seemed like a definitive discovery about why sleep deprivation kills. Working with both flies and mice, they reported that severe sleep deprivation led to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)—highly reactive molecules that can damage cells—specifically in the gut. The findings were compelling: intestinal tissues showed widespread cellular damage, including DNA damage, stress granules, and markers of cell death. When they prevented ROS accumulation using antioxidant compounds or by expressing antioxidant enzymes specifically in the gut, sleep-deprived flies could survive with little to no sleep. The conclusion seemed clear: sleep deprivation kills by causing oxidative damage in the gut.

This discovery was revolutionary because it provided a specific, mechanistic explanation for lethality. It wasn’t just that animals were tired or stressed—there was measurable, progressive damage to a specific organ system. The gut, with its high metabolic activity and regenerative capacity, appeared to be the Achilles heel during prolonged wakefulness.

A Gentler Approach Reveals a Different Truth

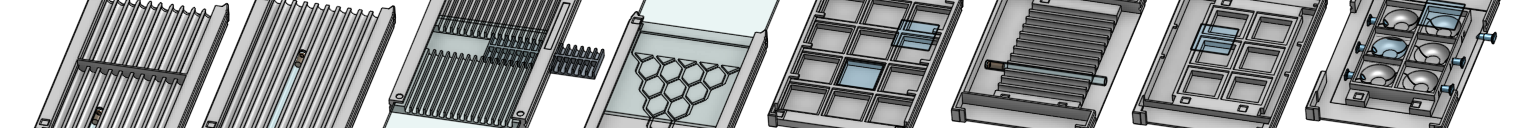

Enter the ethoscope: a clever device that uses real-time video tracking to monitor individual fruit flies. Unlike previous methods that constantly harass animals, the ethoscope only intervenes when it detects that a fly is actually sleeping—giving it a gentle nudge to wake up, then leaving it alone during active periods.

Using this stress-controlled approach, we had already found something remarkable back in 2019: flies could be kept awake throughout their lives without dying!

This raised an intriguing question: if Vaccaro’s team found that sleep deprivation caused lethal ROS accumulation in the gut, why were our flies surviving indefinitely? We hypothesized that our gentler, ethoscope-based sleep deprivation method might not induce the same intestinal oxidative damage.

Testing the ROS Hypothesis

To test this directly, we subjected flies to 10 days of continuous sleep deprivation using the ethoscope and examined their intestinal tissues using the same fluorescent probes used by Vaccaro and colleagues—DHE for superoxide detection and H2DCF for hydrogen peroxide detection. The results were striking: we found no ROS accumulation whatsoever.

But we needed to rule out confounding factors. Perhaps dietary antioxidants or the gut microbiome were masking ROS accumulation by scavenging reactive oxygen species before we could detect them? We systematically eliminated these possibilities:

- We maintained flies on minimal diet consisting only of 5% sucrose in agar, lacking the complex nutrients and natural antioxidants in standard laboratory food—still no ROS.

- We raised axenic flies completely free of microorganisms from embryonic development through adulthood—still no ROS accumulation following sleep deprivation.

- We even performed sleep deprivation at higher temperatures (29°C) to accelerate metabolic rate—still no detectable ROS.

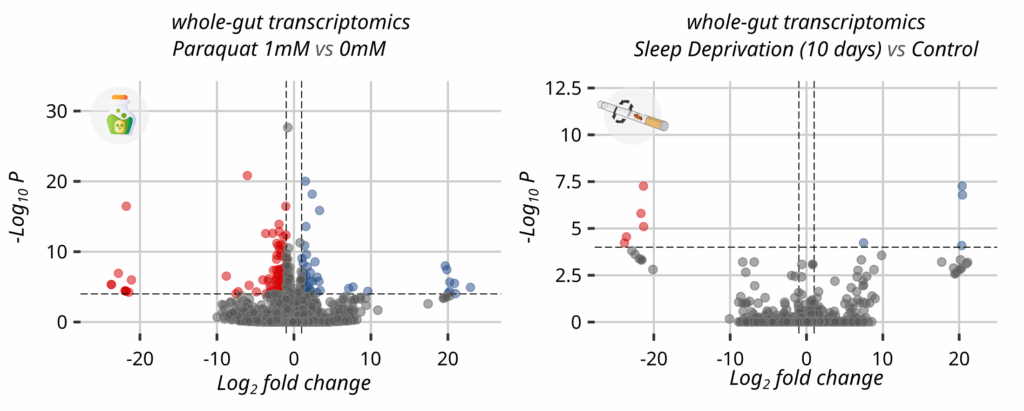

To validate our detection methods, we exposed flies to paraquat, a potent toxin that generates ROS. As expected, even low doses of paraquat produced readily detectable ROS accumulation in the gut. Surprisingly, adding 10 days of sleep deprivation to paraquat treatment produced no additional effect—sleep-deprived animals showed no increase in ROS levels compared to rested controls receiving the same paraquat dose, and no change in survival.

The conclusion was inescapable: ethoscope-based sleep deprivation, even when sustained for 10 days, does not cause intestinal ROS accumulation or oxidative damage.

To strengthen the molecular analysis, we also performed transcriptomic of paraquat-induced oxidative stress versus sleep deprivation. The gene expression patterns were completely distinct, with virtually no overlap between pathways activated by oxidative stress and those activated by sleep loss. If sleep deprivation truly caused oxidative damage, we would expect some molecular convergence—but we found none.

The critical insight is that previous sleep deprivation methods inadvertently confounded sleep loss with physical and psychological stress. The ROS accumulation and lethality observed in these studies likely resulted from the stress of the methodology rather than sleep loss itself.

Stress: The Real Culprit

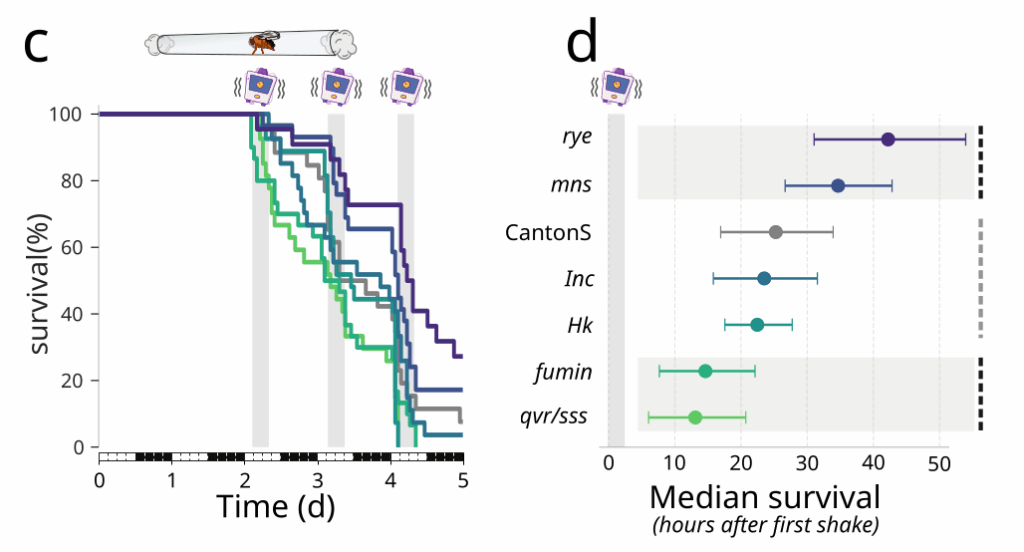

To test this directly, we subjected flies to various forms of stress without depriving them of sleep. The results were striking:

- Physical stress: Just 5 minutes of vigorous shaking per day for 4 days caused intestinal ROS accumulation and death

- Psychological stress: Flies subjected to social defeat (essentially bullying) by dominant flies showed clear signs of oxidative damage

- The same pattern held in mice: Brief restraint stress was enough to trigger intestinal ROS accumulation and damage

These stress paradigms produced the same intestinal phenotype—ROS accumulation, oxidative damage, and ultimately death—that had previously been attributed to sleep loss. But our sleep-deprived flies, kept awake without added stress, showed none of these effects.

The Plot Twist: Sleep Deprivation Creates Vulnerability

Here’s where the story gets interesting. While sleep deprivation alone didn’t kill flies or cause oxidative damage, it did make them more vulnerable to trauma. Sleep-deprived flies were more likely to die when subjected to physical stress, but only under specific conditions.

We subjected flies to two different types of physical force: violent shaking (which constantly changes direction) and centrifugal force (which maintains a steady direction). Both methods applied similar levels of force to the flies, but only the shaking proved lethal. The centrifuge treatment caused no deaths at all. This revealed that it wasn’t the force itself or the procedural stress that was dangerous, but rather the chaotic, multi-directional nature of shaking that caused the trauma.

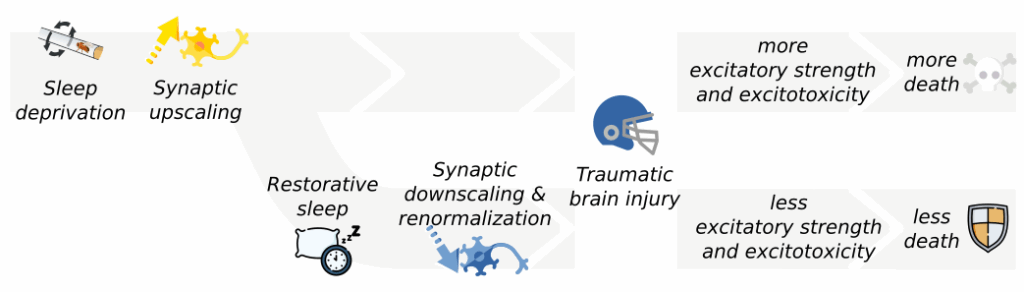

To understand this better, we examined what happened when we combined sleep deprivation with the shaking treatment. We found that flies deprived of sleep for 24 hours showed dramatically increased mortality when subjected to shaking—but this effect disappeared if we allowed them 6 hours of recovery sleep first. Even more intriguingly, when we tested various genetic mutants with naturally short sleep, we discovered something unexpected: their vulnerability to shaking didn’t correlate with how little they slept. Some short-sleeping mutants were actually more resistant to shaking trauma, while others were more vulnerable. The pattern seemed to depend not on sleep duration, but on the specific neural pathways affected by each mutation.

The key turned out to be brain excitability. Sleep deprivation strengthens synapses (the connections between neurons), essentially putting the brain in a hyperactive state. When trauma strikes this “primed” brain, it triggers a cascade of toxic reactions that can prove fatal—exacerbating the violence of a traumatic brain injury. Remarkably, flies with genetic mutations that prevented this synaptic strengthening didn’t show increased vulnerability when sleep-deprived. The problem wasn’t sleep loss itself, but the heightened brain state it created.

What This Means for Humans

This research doesn’t mean you should pull all-nighters without concern. Sleep deprivation in humans causes well-documented problems: impaired cognition, weakened immunity, mood disturbances, and increased accident risk. But these effects might be more about the brain operating in a vulnerable, hyperexcitable state rather than accumulating irreversible damage.

The findings also help explain why stress management is often more effective than simply trying to sleep longer for people with insomnia. Modern sleep medicine increasingly recognizes that stress and sleep problems create vicious cycles—stress disrupts sleep, poor sleep amplifies stress sensitivity, and the cycle continues.

Importantly, while we’ve shown that controlled sleep deprivation doesn’t cause the intestinal ROS accumulation seen in earlier studies, we’re not dismissing the association between sleep loss and gut health. Chronic sleep restriction in real-world scenarios is almost always accompanied by stress, and the combination may indeed lead to oxidative damage. The crucial distinction is that stress, not sleep loss itself, is the primary driver of this damage.

The Bigger Picture

This research represents more than just a correction to sleep science—it’s a reminder of how methodological assumptions can shape entire fields of study. For over a century, the inability to separate sleep loss from stress led researchers down the wrong path.

The Vaccaro study was a major advance in identifying the gut as a critical organ and ROS as a key mechanism in mortality following sleep deprivation paradigms. Our work doesn’t refute those findings—it refines them by demonstrating that the ROS accumulation results from stress inherent in traditional sleep deprivation methods rather than from sleep loss per se.

The real lesson might be that sleep deprivation doesn’t slowly poison us, but rather leaves us vulnerable to life’s inevitable stressors. A sleep-deprived brain isn’t a damaged brain—it’s a primed one, heightened in its responses but fragile when confronted with challenges.

In our stress-filled modern world, perhaps the focus shouldn’t just be on getting eight hours of sleep, but on creating conditions where both stress and sleep can be properly managed together. After all, as this research shows, it might not be the sleep loss that’s the problem—it’s everything else that comes with it.

Hi Giorgio,

It was wonderful attending your talk in Crete on your research on stress, sleep loss, intestinal oxidative damage, and mortality. I’m very interested in reading this paper, but unfortunately I’m unable to access any of the provided links, and I haven’t been able to locate it on bioRxiv either.

Would you be able to share a copy of the paper directly? I’d greatly appreciate it.

Best regards,

Farhan

Oops. I had not realised this preview had been flagged as public already in June – that was a mistake. We’ll upload a preprint on biorxiv probably next week!