What has changed in science and what must change.

I frequently have discussions about funding in Science (who doesn’t?) but I realized I never really formalized my ideas about it. It makes sense to do that here. A caveat before I start is that everything I write about here concerns the field of bio/medical sciences for those are the ones I know. Other fields may work in different ways. YMMV.

First of all, I think it is worth noticing that this is an extremely hot topic, yet not really controversial among scientists. No matter whom you talk to, not only does everyone agree that the status quo is completely inadequate but there also seem to be a consensus on what kind of things need to be done and how. In particular, everyone agrees that

- more funding is needed

- the current ways of distributing funding and measuring performance are less than optimal

When everybody agrees on what has to be done but things are not changing it means the problem is bigger than you’d think. In this post I will try to dig deeper into those two points, uncovering aspects which, in my opinion, are even more fundamental and controversial.

Do we really need more funding?

The short answer is yes but the long answer is no. Here is the paradox explained. Science has changed dramatically in the past 100, 50 (or even 10) years, mainly because it advances at a speedier pace than anything else in human history and simply enough we were (and are) not ready for this. This is not entirely our fault since, by definition, every huge scientific breakthrough comes as a utter surprise and we cannot help but be unprepared to its consequences¹. We did adapt to some of the changes but we did it badly and we did not do it for all to many aspects we had to. In short, everyone is aware about the revolution science has had in the past decades, yet no one has ever heard of a similar revolution in the way science is done.

A clear example of something we didn’t change but we should is the fundamental structure of Universities. In fact, that didn’t change much in the past 1000 years if you think about it. Universities still juggle between teaching and research and it is still mainly the same people who does both. This is a huge mistake. Everybody knows those things have nothing in common and there is no reason whatsoever for them to lie under the same roof. Most skilled researchers are awful teachers and viceversa and we really have no reason to assume it should not be this way Few institutions in the world concentrate fully on research or only teaching but this should not be the exception, it should be the rule. Separating teaching and research should be the first step to really be able to understand the problems and allocate resources.

Tenure must also be completely reconsidered. Tenure was initially introduced as a way to guarantee academic freedom of speech and action. It was an incentive for thoughtful people to take a position on controversial issues and raise new ones. It does not serve this role anymore: you will get sacked if you claim something too controversial (see Lawrence Summers’ case) and your lab will not receive money if you are working on something too exotic or heretic. Now, I am not saying this is a good or a bad thing. I am just observing that the original meaning of tenure is gone. Freedom of speech is something that should be guaranteed to everyone, not just academic, through constitutional laws and freedom of research is not guaranteed by tenure anyway because you don’t get money to do research from your university, you just get your salary. It’s not 1600 anymore, folks.

Who is benefiting from tenure nowadays? Mainly people who have no other meaning of paying their own salary, that is researchers who are not active or poorly productive and feel no obligation to do so because they will get their salary at the end of the month anyway. This is the majority of academic people not only in certain less developed countries – like Italy, sigh – but pretty much everywhere. Even in the US or UK or Germany many departments are filled with people who publish badly or scarcely. Maybe they were good once, or maybe it was easier at their time to get a job. Who pays for their priviledge? The younger generation, of course.

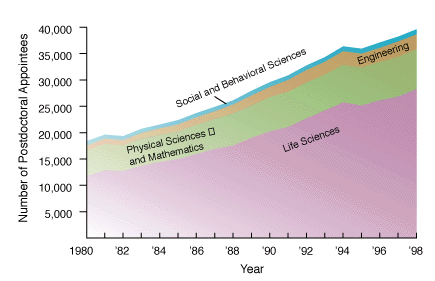

The number of people entering science grows every year², especially in the life sciences. The number of academic position and the funding extent is far from being sufficient to cover current needs. In fact, about 1-2 in 10 postdoc will manage to find a job as professor and among those who do, funding success rate is again 20-30% in a good year. In short, even if we were to increase the scientific budget by 5 times tomorrow morning that would still not be enough. This means that even though it would be sure nice to have more money, it’s utopia to think this will help. Indeed, we need to revolutionize everything, really. People who have tenure should not count on it anymore and they should be ready to leave their job to somebody else. There is no other way, sorry.

Do we really need better forms of scientific measurement?

No. We need completely new forms of scientific measurement. And we need to change the structure of the lab. Your average successful lab is composed of 10 to 30 members, most of them PhD students or postdocs. They are the ones who do the work, without doubts. In many cases, they are the ones who do the entire work not only without their boss, but even despite the boss. This extreme eventuality is not the rule, of course, but the problem is: there is no way to tell it apart! The principal investigator as they say in the USA, or the group leader as it is called with less hypocrisy in Europe, will spend all of their time writing grants to be funded, speaking at conferences about work they didn’t do, writing or merely signing papers. Of course leading a group takes some rare skills, but those are not the skill of a scientist they are the skills of a manager. The system as it is does not reward good scientists, it rewards good managers. You can exploit creativity of the people working for you and be succesful enough to keep receiving money and be recognized as a leader but you are feeding a rotten process. Labs keep growing in size because postdocs don’t have a chance to start their own lab and because their boss uses their work to keep getting the money their postdoc should be getting instead. This is an evil loop.

This is a problem that scientometrics cannot really solve because it’s difficult enough to grasp the importance of a certain discovery, let alone the actual intellectual contribution behind it. It would help to rank laboratories not just by number of good publications, but by ratio between good papers and number of lab members. If you have 1 good paper every second year and you work alone, you should be funded more than someone who has 4 high publications every year but has a group of 30 people.

Some funding agencies, like HHMI, MRC and recently WellcomeTrust, decided to jump the scientometric problem and fund groups independently of their research interest: they say “if you prove to be exceptionally good, we give you loads of money and trust your judgement”. While this is a commendable approach, I would love to see how those labs would rank when you account for number of people: a well funded lab will attract the best sutudents and postdocs and good lab members make a lab well funded. Here you go with an evil loop again.

In gg-land, the imaginary nation I am supreme emperor of, you can have a big lab but you must really prove you deserve it. Also, there are no postdocs as we know them. Labs have students who learn what it means to do science. After those 3-5 years either you are ready to take the leap and do your stuff by yourself or you’ll never be ready anyway. Don’t kid yourself. Creativity is not something you can gain with experience; if at all, it’s the other way around: the older you get, the less creative you’ll be.

Some good places had either a tradition (LMB, Bell labs) or have the ambition (Janelia) of keeping group small and do science the way it should be done. Again, this should not be the exception. It should be the rule. I salute with extreme interest the proliferation of junior research fellowships also known as independent postdoc positions. They are not just my model of how you do a postdoc. In fact they are my model of how you do science tout court. Another fun thing about doing science with less resource is that you really have to think more than twice about what you need and spend your money more wisely. Think of the difference between buying your own bike or building one from scratch. You may start pedaling first if you buy one, but only in the second case you will have a chance to build a bike that run faster and better. On the long run, you may well win the race (of course you should never reinvent the wheel; it’s OK to buy those).

Of course, the big advantage of having many small labs over few big is that you get to fund different approaches too. As our grandmother used to say: it’s not good to keep all eggs in the same basket. As it happens in evolution, you have to diversify, in science too³.

What can we (scientists) do? Bad news is, I don’t think these are problems that can be solved by scientists. You cannot expect unproductive tenure holders to give up their job. You cannot expect a young group leader to say no to tenure, now that they are almost there. You cannot expect a big lab to agree in reducing the number of people. Sure, all of them complaint that they spend their times writing grants and cannot do the thing they love the most – experiments! – anymore because too busy. If you were to give them the chance to go back to the bench again, they would prove as useless as an undergrad. They are not scientists anymore, they are managers. These are problem that only funding agencies can solve, pushed by those who have no other choice that asking for a revolution, i.e.: the younger generation.

Notes:

1. Surprise is, I believe, the major difference between science and technology. The man on the moon is technology and we didn’t get there by surprise. Penicillin is science and comes out of the blue, pretty much.

2. Figure is taken from Mervis, Science 2000. More recent data on the NSF website, here.

3. See Michael Nielsen’s post about this basic concept of life.

Update:

Both Massimo Sandal and Bjoern Brembs wrote a post in reply to this, raising some interesting points. My replies are in their blogs as comments.

I bet that no matter whom you talk to, people will always tell you that there is not enough money and that the way of distributing money is not optimal, also outside the scientific world. I would not put that emphasis on the fact that in the scientific field people complain about money; it is part of the human nature more than a problem of the field itself

I quite disagree on that. It may be true that the best teacher is not the best researcher, and viceversa, yet they should be always related and a constant communication between the two fields is required. How can you teach to be a good researcher if you never made research? A good way to implement this communication may be within the same institution, that is the University.

I come from the technological/scientific world, and i really do not understand this major difference. I believe bio/medical science is different, but in my field (Aerospace NdB) research and technology are pretty much related, and science does not come out of the cylinder as a surprise or because of creativity.

“I would not put that emphasis on the fact that in the scientific field people complain about money; it is part of the human nature more than a problem of the field itself”

Thing to stress here is that everyone agrees we need more money but nobody ever tells you that even if we had twice or 4x as much we’d still be stuck with the same issue. Everyone in the UK was “celebrating” the lack of cuts over scientific budget couple of weeks ago: little does it matter than it still leaves us in a street that has no way out.

“they should be always related and a constant communication between the two fields is required.” Says who? As a student, you would be better off with a good teacher who can explain to you Plank’s equations and then you should be prompted to follow the latest development in aeronautics on the journals or on freely available seminars on the web.

” and science does not come out of the cylinder as a surprise or because of creativity.” True. Mainly because of serendipity. The point is that technological development suffered less because people are more ready and prepared about changes.

[…] have been pointed today by my friend and brilliant scientist Giorgio Gilestro to an interesting blog post of his on how science should change. My reaction was “This is really really interesting and […]

Hi Giorgio,

You can find a first response on my blog:

http://blog.devicerandom.org/2010/12/01/what-has-changed-in-science-and-what-must-change-i-rethink-the-scientific-career/

thanks for the conversation spark! I hope a dialogue ensues with more and more people.

I can answer here to a small point: I also disagree strongly with separating teaching and research.

That “specialized teaching” is not useful in giving better teaching is known by anyone who has been in high school. And anyone who has been in high school and university, if remembers both periods, can tell why university teaching is often hugely better than school teaching: Because you have people teaching you who are the people who actually do stuff and therefore have an insight which a mere repeater of concepts can’t have.

And yes, often good scientists are good teachers (and good speakers at conferences too). In my experience the two things are truly correlated. Which is no surprise: To be a good teacher you have to understand a subject in its essence and to be able to visualize it in your mind in full clarity. And that’s the same essential conceptual skill you need for science.

I agree however that many basic 1st-year courses wouldn’t need probably a proper researcher doing them. But when you begin to teach something that’s beyond the very rudimental basics, you want someone who *does* the stuff.